By

Margaretta wa Gacheru (posted December 13, 2018)

You can spot

a Joseph Cartoon painting anywhere this industrious Banana Hill artist is

exhibiting his art. Currently, that is at the Red Hill Gallery where his

one-man show spans decades of his paintings.

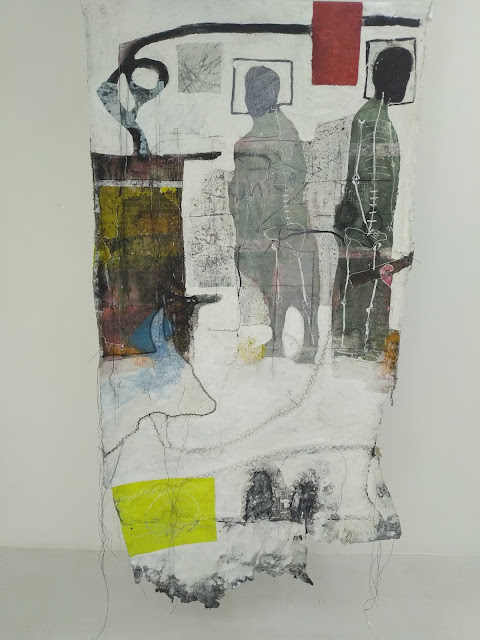

Cartoon’s

distinctive style is colorful, flamboyant and filled with a dizzying array of

designs. He’s got everything from polka dots, strips and plaids to patterns

that are geometric, floral and checkered in his art. Often, he will pour many

of those shapes and designs into a single painting with each pattern painted in

a minimum of two colors.

And while

there might seem to be a sameness to Cartoon’s style of decorative painting, if

one looks closely, you will see that every artwork is different. The patterns,

colors and shapes are also distinct.

What is the

same in his art is that Cartoon rarely if ever lets go of the image of rural

women tightly integrated into a single work. His village women’s interaction on

canvas is practically surreal since they all seem to have a role to play except

that all but one tends to be intact. The others are visible as a head, a leg or

a hand. It’s a style that provokes a query: are there reasons for their

dismemberment or is he just playing around with painting body parts?

Either way,

it really doesn’t matter since one appreciates Cartoon for the increasing

complexity of his work. His early works, which Hellmuth Rossler-Musch began

collecting back in the 1990s is far less complex (some would say ‘busy’) than

the works he is painting now.

Nearly half

the artwork in the Red Hill Gallery show are early works of Cartoon’s, created

when the artist was just starting out. That was when he was still very much a

young ‘disciple’ of Shine Tani who at the time was heading the Banana Hill arts

studio.

Cartoon

arrived at the studio without a day’s experience of painting or drawing. But he

got along well with the artists working together at Banana Hill. So well that

they gave him the nickname ‘Cartoon’ because he was such a funny young guy.

Clearly the name stuck.

Cartoon stayed at the studio long enough to get a fair amount of mentoring from Shine and other artists who were part of Banana Hill artists in those early days, artists like Martin Kamunyu, Joe Friday, John Kimani aka Silver and many others. He got good enough to participate in a number of group shows with them.

Cartoon stayed at the studio long enough to get a fair amount of mentoring from Shine and other artists who were part of Banana Hill artists in those early days, artists like Martin Kamunyu, Joe Friday, John Kimani aka Silver and many others. He got good enough to participate in a number of group shows with them.

But Cartoon

is also an adept businessman. So he also got busy developing a wide array of

business prospects. In the course of it all, he also won a slew of awards,

including a two year art residency in the UK.

Fortunately,

Cartoon’s exhibition at Red Hill is up through January so you can come and

appreciate the intricacies of his art, especially the close attention he gives

to rural women who he clearly esteems or they wouldn’t be the centre of his

focus in so much of his art.

And if you

happen to arrive at Red Hill right when Cartoon is also there, you are bound to

hear illuminating stories about these industrious working women and how at

Chairman Mao used to say, “Women hold up half the sky.”